Ray Dalio is an American billionaire investor. He founded one of the biggest hedge funds in the world—Bridgewater Associates—in New York in 1975.

“Having the basics—a good bed to sleep in, good relationships, good food, and good sex—is most important.”

Ray Dalio

I. Fundamental Principles

Think for yourself to decide 1) what you want, 2) what is true, and 3) what you should do to achieve #1 in light of #2 . . . . . . and do that with humility and open-mindedness so that you consider the best thinking available to you.

I saw that the only way I could succeed would be to:

1. Seek out the smartest people who disagreed with me so I could try to understand their reasoning.

2. Know when not to have an opinion.

3. Develop, test, and systemize timeless and universal principles.

4. Balance risks in ways that keep the big upside while reducing the downside.

I had always wanted to have—and to be around people who also wanted to have—a life full of meaningful work and meaningful relationships, and to me a meaningful relationship is one that’s open and honest in a way that lets people be straight with each other. I never valued more traditional, antiseptic relationships where people put on a façade of politeness and don’t say what they really think.

II. Reality, Nature, and Painful Problems

Reality

To acquire principles that work, it’s essential that you embrace reality and deal with it well. Don’t fall into the common trap of wishing that reality worked differently than it does or that your own realities were different. Instead, embrace your realities and deal with them effectively. After all, making the most of your circumstances is what life is all about. This includes being transparent with your thoughts and open-mindedly accepting the feedback of others. Doing so will dramatically increase your learning.

Understanding, accepting, and working with reality is both practical and beautiful. I have become so much of a hyperrealist that I’ve learned to appreciate the beauty of all realities, even harsh ones, and have come to despise impractical idealism.

I have found the following to be almost always true: Dreams + Reality + Determination = A Successful Life.

Idealists who are not well grounded in reality create problems, not progress.

Nature

Man is just one of ten million species and just one of the billions of manifestations of the forces that bring together and take apart atoms through time. Yet most people are like ants focused only on themselves and their own anthill; they believe the universe revolves around people and don’t pay attention to the universal laws that are true for all species.

It is a reality that each one of us is only one of about seven billion of our species alive today and that our species is only one of about ten million species on our planet. Earth is just one of about 100 billion planets in our galaxy, which is just one of about two trillion galaxies in the universe. And our lifetimes are only about 1/3,000 of humanity’s existence, which itself is only 1/20,000 of the Earth’s existence.

For me personally, I now find it thrilling to embrace reality, to look down on myself through nature’s perspective, and to be an infinitesimally small part of the whole. My instinctual and intellectual goal is simply to evolve and contribute to evolution in some tiny way while I’m here and while I am what I am. At the same time, the things I love most—my work and my relationships—are what motivate me. So, I find how reality and nature work, including how I and everything will decompose and recompose, beautiful— though emotionally I find the separation from those I care about difficult to appreciate.

For most people, success is struggling and evolving as effectively as possible, i.e., learning rapidly about oneself and one’s environment, and then changing to improve.

Painful Problems

It is a fundamental law of nature that in order to gain strength one has to push one’s limits, which is painful. As Carl Jung put it, “Man needs difficulties. They are necessary for health.” Yet most people instinctively avoid pain. This is true whether we are talking about building the body (e.g., weight lifting) or the mind (e.g., frustration, mental struggle, embarrassment, shame)—and especially true when people confront the harsh reality of their own imperfections.

There is no avoiding pain, especially if you’re going after ambitious goals. Believe it or not, you are lucky to feel that kind of pain if you approach it correctly, because it is a signal that you need to find solutions so you can progress. If you can develop a reflexive reaction to psychic pain that causes you to reflect on it rather than avoid it, it will lead to your rapid learning/evolving. After seeing how much more effective it is to face the painful realities that are caused by your problems, mistakes, and weaknesses, I believe you won’t want to operate any other way. It’s just a matter of getting in the habit of doing it.

The challenges you face will test and strengthen you. If you’re not failing, you’re not pushing your limits, and if you’re not pushing your limits, you’re not maximizing your potential. Though this process of pushing your limits, of sometimes failing and sometimes breaking through—and deriving benefits from both your failures and your successes—is not for everyone, if it is for you, it can be so thrilling that it becomes addictive. Life will inevitably bring you such moments, and it’ll be up to you to decide whether you want to go back for more.

Having a process that ensures problems are brought to the surface, and their root causes diagnosed, assures that continual improvements occur.

If you can be open with your weaknesses it will make you freer and will help you deal with them better. I urge you to not be embarrassed about your problems, recognizing that everyone has them. Bringing them to the surface will help you break your bad habits and develop good ones, and you will acquire real strengths and justifiable optimism.

III. Goals, Decision Making, and Open Mindedness

Goals

Choosing a goal often means rejecting some things you want in order to get other things that you want or need even more. Some people fail at this point, before they’ve even started. Afraid to reject a good alternative for a better one, they try to pursue too many goals at once, achieving few or none of them. Don’t get discouraged and don’t let yourself be paralyzed by all the choices. You can have much more than what you need to be happy. Make your choice and get on with it.

Remember that great expectations create great capabilities. If you limit your goals to what you know you can achieve, you are setting the bar way too low.

Write down your plan for everyone to see and to measure your progress against. This includes all the granular details about who needs to do what tasks and when. The tasks, the narrative, and the goals are different, so don’t mix them up. Remember, the tasks are what connect the narrative to your goals. Recognize that it doesn’t take a lot of time to design a good plan. A plan can be sketched out and refined in just hours or spread out over days or weeks. But the process is essential because it determines what you will have to do to be effective. Too many people make the mistake of spending virtually no time on designing because they are preoccupied with execution. Remember: Designing precedes doing!

Decision Making

Think of every decision as a bet with a probability and a reward for being right and a probability and a penalty for being wrong.

The two biggest barriers to good decision making are your ego and your blind spots. Together, they make it difficult for you to objectively see what is true about you and your circumstances and to make the best possible decisions by getting the most out of others. If you can understand how the machine that is the human brain works, you can understand why these barriers exist and how to adjust your behavior to make yourself happier, more effective, and better at interacting with others.

Open Mindedness

Let’s look at what tends to happen when someone disagrees with you and asks you to explain your thinking. Because you are programmed to view such challenges as attacks, you get angry, even though it would be more logical for you to be interested in the other person’s perspective, especially if they are intelligent. When you try to explain your behavior, your explanations don’t make any sense. That’s because your lower-level you is trying to speak through your upper-level you. Your deep-seated, hidden motivations are in control, so it is impossible for you to logically explain what “you” are doing. Even the most intelligent people generally behave this way, and it’s tragic. To be effective you must not let your need to be right be more important than your need to find out what’s true. If you are too proud of what you know or of how good you are at something you will learn less, make inferior decisions, and fall short of your potential.

Sincerely believe that you might not know the best possible path and recognize that your ability to deal well with “not knowing” is more important than whatever it is you do know. Most people make bad decisions because they are so certain that they’re right that they don’t allow themselves to see the better alternatives that exist. Radically open-minded people know that coming up with the right questions and asking other smart people what they think is as important as having all the answers. They understand that you can’t make a great decision without swimming for a while in a state of “not knowing.” That is because what exists within the area of “not knowing” is so much greater and more exciting than anything any of us knows.

IV. AND1—Neuroscience, Habits, and Change

Neuroscience

All of our thinking and feeling is due to physiology (in other words, the chemicals, electricity, and biology in our brains working like a machine).

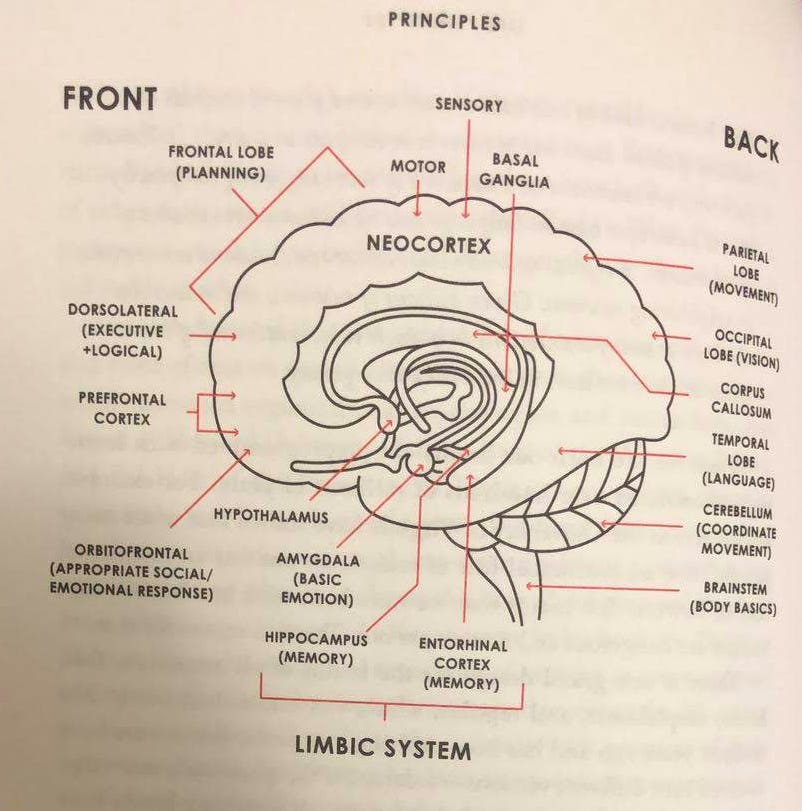

Your deepest-seated needs and fears— such as the need to be loved and the fear of losing love, the need to survive and the fear of not surviving, the need to be important and the fear of not mattering—reside in primitive parts of your brain such as the amygdala, which are structures in your temporal lobe that process emotions. Because these areas of your brain are not accessible to your conscious awareness, it is virtually impossible for you to understand what they want and how they control you. They oversimplify things and react instinctively. They crave praise and respond to criticism as an attack, even when the higher-level parts of the brain understand that constructive criticism is good for you. They make you defensive, especially when it comes to the subject of how good you are.

This “universal brain” has evolved from the bottom up, meaning that its lower parts are evolutionarily the oldest and the top parts are the newest. The brainstem controls the subconscious processes that keep us and other species alive—heartbeat, breathing, nervous system, and our degree of arousal and alertness.

The next layer up, the cerebellum, gives us the ability to control our limb movements by coordinating sensory input with our muscles.

Then comes the cerebrum, which includes the basal ganglia (which controls habit) and other parts of the limbic system (which controls emotional responses and some movement) and the cerebral cortex (which is where our memories, thoughts, and sense of consciousness reside).

The newest and most advanced part of the cortex, that wrinkled mass of gray matter that looks like a bunch of intestines, is called the neocortex, which is where learning, planning, imagination, and other higher-level thoughts come from. It accounts for a significantly higher ratio of the brain’s gray matter than is found in the brains of other species.

Habits

Habit is probably the most powerful tool in your brain’s toolbox. It is driven by a golf-ball-sized lump of tissue called the basal ganglia at the base of the cerebrum. It is so deep-seated and instinctual that we are not conscious of it, though it controls our actions. If you do just about anything frequently enough over time, you will form a habit that will control you.

Good habits are those that get you to do what your “upper-level you” wants, and bad habits are those that are controlled by your “lower-level you” and stand in the way of getting what your “upper level you” wants.

Habit is essentially inertia, the strong tendency to keep doing what you have been doing (or not doing what you have not been doing). Research suggests that if you stick with a behavior for approximately eighteen months, you will build a strong tendency to stick to it nearly forever.

Change

Understand how much the brain can and cannot change. This brings us to an important question: Can we change? We can all learn new facts and skills, but can we also learn to change how we are inclined to think? The answer is a qualified yes. Brain plasticity is what allows your brain to change its “soft wiring.” For a long time, scientists believed that after a certain critical period in childhood, most of our brain’s neurological connections were fixed and highly unlikely to change. But recent research has suggested that a wide variety of practices —from physical exercise to studying to meditation—can lead to physical and physiological changes in our brains that affect our abilities to think and form memories.

Successful people change in ways that allow them to continue to take advantage of their strengths while compensating for their weaknesses and unsuccessful people don’t.