How I Achieved a C1 Level in Spanish (Advanced Fluency)

The short answer and the long answer

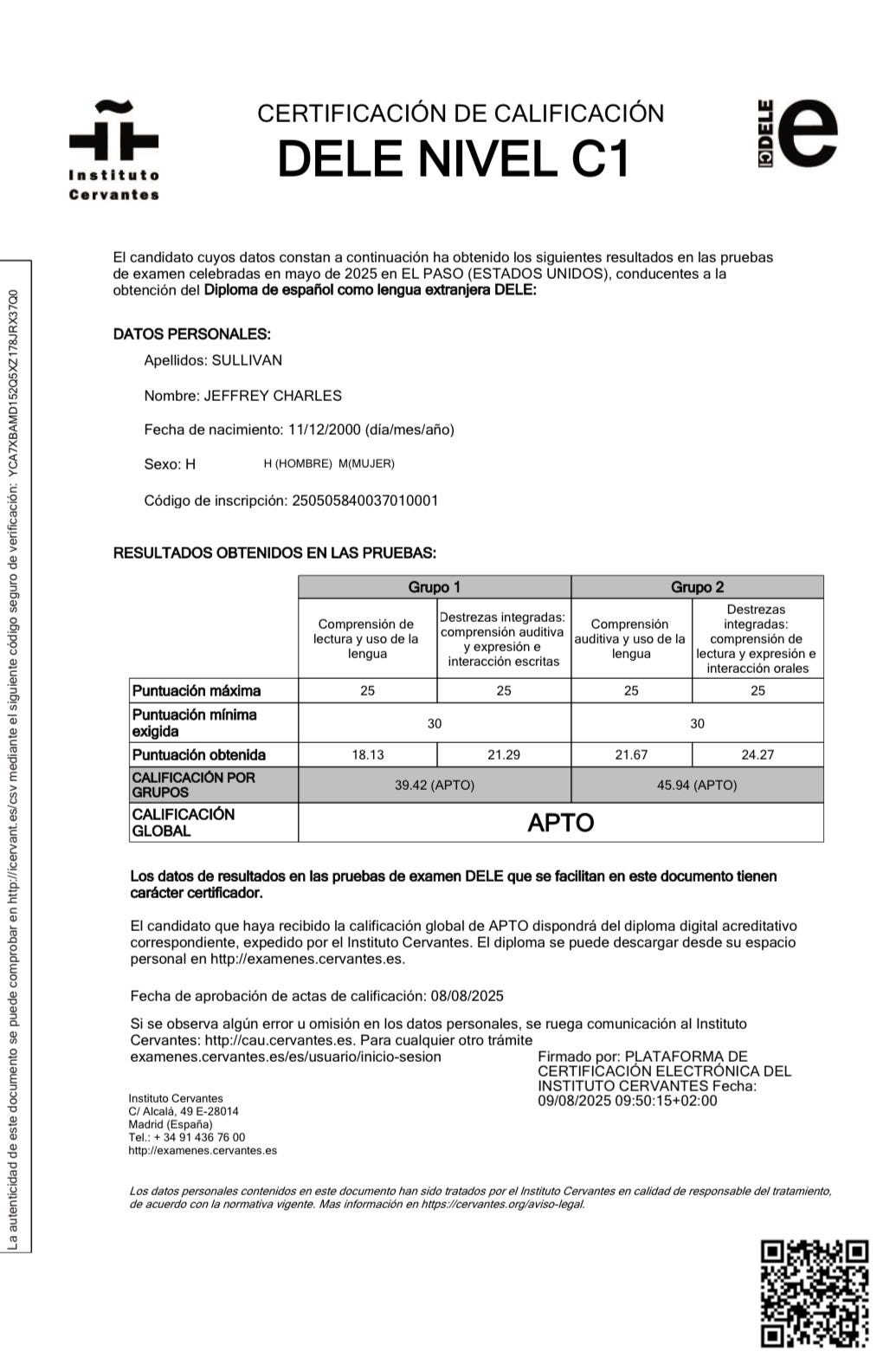

I recently achieved a longtime goal of mine: an advanced DELE Spanish language diploma.

This certification comes from Instituto Cervantes, a nonprofit organization created by the government of Spain in 1991 to promote the use of Spanish.

According to the institute, the C1 Spanish Diploma certifies the language user’s ability to:

express yourself fluently, spontaneously, and effortlessly;

proficiently process a wide variety of oral and written texts of a certain length in any variant of the language, even recognizing implicit meanings, attitudes, or intentions;

always find the appropriate expression for the situation and context, whether social, professional, or academic; and

use the language flexibly and effectively, demonstrating correct use in the creation of complex texts and in the use of organizational and cohesive mechanisms that allow them to be articulated.

Why did I want to do it?

The main reason I wanted this certification and have dedicated so much time and effort to learning Spanish is simple: because it is fun.

Everyone I know who has developed exceptional ability in another language has this in common. They actually enjoy the process. This is the most important thing. Whether it is trying to understand what someone said, figuring out the proper pronunciation of a phrase, or knowing the correct conjugation of a certain verb in a certain tense, these are the types of puzzles their brain likes to solve, just as some people get a kick out of solving mathematical equations or crosswords.

Now, that does not mean learning another language is all sunshine and rainbows. Without a doubt, there were some parts of Spanish classes over the years in high school and college—like the “impersonal se” or subjunctive—that I struggled with and didn’t like as much as other topics. But overall, I still liked going to most of these classes and practicing in my own time.

Additionally, apart from taking pleasure in the process itself, one of the other main reasons I’ve always liked learning Spanish is that I had a why.1 Through the years, I would visualize myself in the streets of Barcelona or Buenos Aires or wherever else, smoothly speaking Spanish at the coffee shop, bar, beach and beyond. I would visualize myself leveraging Spanish to advance my career. I would visualize myself recording podcast episodes in Spanish. And lo and behold, those are things that ended up happening in reality.

But before all those great moments came, there were moments of embarrassing mispronunciations, tedious grammar study, and awkward misunderstanding after awkward misunderstanding. However, in the end, they were mere road bumps, and I refused to let them stop me from getting to where I was going. In the immortal words of Nietzsche, “he who has a why can bear almost any how.”

This is important to note because I’m not aware of anyone who doesn’t like the idea of learning another language, particularly Spanish. But once they start getting into the weeds—like, say, knowing which verbs are irregular in the preterite tense—they lose interest, and their desire to keep going fades. But if you have a why, that is way less likely to happen. You push through. Like a bodybuilder committed to becoming the strongest version of themselves, you do it even when it sucks, even when it feels hard.

That said, I must note that there is also the reality that learning a language just isn’t for some people. We’re all wired differently. It’s funny how much the human mind can like the idea of doing something but not like actually doing it, and vice versa. For example, because I strive (in vain) to be a Renaissance Man, I like the idea of learning physics at a deeper level. But every time I open a physics book, I’m met with a sense of profound boredom and confusion. And I don’t have a strong enough why to push through. I suspect this is the experience a lot of people have with languages. Which, if that seems to apply to you, you should not beat yourself up about it, and instead focus on things that light you up with excitement and come more naturally to you. But, as a crucial side note, I think this experience would happen way less if people focused on speaking the language way earlier, because that is the most fun part, and is what ultimately encourages you to keep learning more. Unfortunately, as beneficial as many of them were for me, I’ve observed that for many people, language classes and textbooks are where Spanish fluency dreams go to die. You need a certain level of formal instruction to have a solid baseline of knowledge, but every language learner benefits from having conversations with native speakers more often, no matter how simple of an exchange.

To go back to why I took the C1 exam for a moment, I wanted my fluency to be “official.” Let me be clear here: I love when I’m talking to someone and they tell me they know or are learning another language. Just as a shared favorite book can instantly make you friendly with someone you just met, seeing that they are a fellow language learner does the same. It sends a certain signal about what type of person they likely are: curious, open-minded, smart.

However, there are far too many people out there I’ve come across, both in person and on the internet, who say they “speak Spanish” or are “fluent,” when, in reality, their level is not very high at all. I hesitate to criticize people like this, because I think I was guilty of doing the same at one point or another in college. I first felt confident enough to say I spoke Spanish during my sophomore year, and while I did speak it pretty well then, if I listen to a recording or video of myself from that era, I cringe a bit.

The point is that, with a C1 certification from Instituto Cervantes, your fluency is undeniable. In fact, most people consider B2, the level right below C1, as the threshold for fluency. So C1 is more about advanced proficiency. The only level higher than C1 is C2, which is the “native-like” level. I attempted taking the C2 exam last year in New York City, but did not pass. I think that to be C2, you have to live in a Spanish-speaking country for longer than I’ve had the opportunity to so far in my life. But the fact I did okay enough on C2 gave me enormous confidence I could crush C1, which was clearly a more achievable goal. Although C2 is the black belt, I’m content with my brown belt. And maybe there will come a time when I dare to retake the daunting C2 exam.2

So with all that said, let’s get into the details of how I got here in the first place.

How did I do it?

The short answer is that I worked very hard on learning the language for a really long time.

You see, the internet is full of grifters lying to you about how they LEARNED SPANISH IN 30 DAYS; I have nothing like that to offer you. I took classes throughout all of middle school, high school, and college.3 I took the AP national exam when I was 18, studied abroad in Spain when I was 21, and, as mentioned, took both the C2 and C1 exams from Instituto Cervantes when I was 23 and at my current age of 24. All of this was necessary for getting to where I am now.

But what actions, habits, and strategies specifically moved the needle on my Spanish skill? I’m not going to pretend like I can give you all the answers and everything you need to learn it in a single blog post, but I will tell you what worked for me, and you can potentially use that.

The simple fact is that the number one contributing factor to my Spanish competency has been time and reps.

But what kind of reps? Well, first is just showing up to Spanish class every day. If you’re in high school or college or working with a tutor, you definitely should keep doing that. Sure, there are more “optimal” ways to learn, but consistent exposure to the language is only going to help in the long run.

Spanish class just can’t be the only thing you do.

In my free time, there were four specific habits that helped the most, and they all relate to one of the four elements of language learning: reading, writing, listening and speaking. My biggest leaps in progress were made as a college student who practiced more online than in person. It is of course more ideal, fun, and effective to have conversations in the good old physical world, but you don’t necessarily need to live or travel to a foreign country to speak and be immersed in a language.

So, let’s start with the listening element. For training my ear, I turned my iPhone into a Latin land of digital immersion through YouTube videos, podcasts, and music. At first, I listened a lot to the podcast Easy Spanish, and eventually graduated to content made for native speakers, as opposed to content made for language learners. For example, I enjoy and still listen to Curiosidades de la Historia National Geographic.4

Moving on to the reading element, it is sometimes hard enough to read in your mother tongue, so it can feel daunting to take it up in another language. It is, however, important if you want to become fluent. I’ve read a few books in Spanish, but more than anything, at least recently, it has been reading El País or the New York Times in Spanish (El Times), which exercises this mental muscle. Volume, volume, volume.

When it comes to the writing element, it is definitely underrated how much it can help you in a language. Throughout college, I wrote a decent amount of essays in Spanish for class, and sometimes I’ll journal in it for fun. That said, this is probably the language element I use the least. I already had a baseline of years of language exposure that led to me writing intuitively for class and in my journal, so I don’t know the best way to tell someone how to do this.5

Finally, the habit relating to the speaking element is what transformed my Spanish level more than anything. Having conversations whenever I had the chance—no matter how uncomfortable it was—as well as finding people to speak with online, is the ultimate key.

To find people to speak your target language with online, Tandem and HelloTalk are great options. They are essentially social media sites specifically for language learning. As far as I know, it is the easiest place you can consistently contact and have conversations with native speakers, without having to actually live in a different country. You can translate texts with a tap and make calls within the app. But best of all, it makes it easy to start sending voice messages back and forth with native speakers.

The ideal way to use Tandem or HelloTalk: Type out a message like, “Hi, I’m going to Mexico soon, can I practice my Spanish with you? I can help you with English.” Copy it. Paste to as many people on the app as your thumbs can bear. When people answer, send a voice message of things you wrote down. When they respond with questions, it is another opportunity to say new things. This is how you get comfortable moving your tongue in the way of a different language, and crucially, expanding your vocabulary and conjugation precision. Over time, as you gain confidence through reps on reps, you can make a call. That is a huge jump—going from only exchanging voice messages to making calls—but a necessary one to get to, say, a B2 or C1 level.

Of course, you could just maximize your in-person practice. But consider a few advantages of also doing this online work as a supplement: first, it is much lower stakes. Going to approach a stranger with a question in the street in Costa Rica or wherever you are can be intimidating—and while you do want to get to that point where you can do that without thinking twice—if you trip up in a voice message, you can just delete it and send another one, no big deal. And similarly, if you get to a point where you have phone calls with someone to practice, they themselves being a language learner of English, they’re more likely to be patient, understanding, and compassionate to language learners.

What’s more, Spanish speakers are, as a rule, thrilled when someone is learning the language. Even a little bit of it here and there often brings a smile and encouragement.

Ultimately, the meta message here remains: I got to C1 because I did the thing, a lot, for a very long time.6 Consider what the economist Bryan Caplan writes in his article Do Ten Times As Much:

“How does fluency happen? First and foremost, people who attain fluency practice a lot more than the typical foreign language student. “A lot” doesn’t mean 10% more, 25% more, or even 100% more. People who attain fluency practice about ten times as much as the typical person who is officially “learning a foreign language.” Sure, the quality of practice matters, too; immersion is the best method of foreign language acquisition. But unless you’re willing to give ten times the normal level of effort, fluency is basically a daydream.

When I see the contrast between people who succeed and fail, I generally witness a similar gap in effort. During my eight years in college, I spent many thousands of hours reading about economics, politics, and philosophy. Since high school, I’ve spent over ten thousand hours writing. When young people ask me, “How can I be like you?“ my first thought is, again, do ten times as much.”

People radically underestimate how much it takes to become fluent in a different language. I say this not to discourage anyone but to hopefully splash some reality into the sea of delusion regarding language learning that exists online. Getting to the level of basic conversations is a worthy goal. But to get to the higher levels requires serious commitment. It is a type of commitment I would recommend to anyone, because of how much of a positive impact it has had on my life. But it is just that: a commitment. Just as you’re not going to have a good jump shot if you don’t shoot that much and aren’t consistent in showing up, you’re not going to become fluent dilly-dallying around on Duolingo every few days. Everyone knows this about skill development in general, yet it feels like it needs to be said about languages. It seems this stems from the misconception of what being fluent in another language means.

Think about yourself for a second. All of your complexities and nuances and likes and dislikes and desires and quirks and thoughts and tones of voice and humor and everything that goes on in that interesting brain of yours. Now think about trying to express all that—all of you—in another language. It probably sounds crazy hard to do, right?

Well, exactly that was always my goal with Spanish: to be able to be fully myself in it. Now, that is virtually impossible, especially because I didn’t take learning it seriously until I was eighteen. Everyone I know who learned another language later in life—as opposed to being raised with it as a child—will always be more themselves in their native language. The point is that, being fluent means there’s not too enormous a difference between you in your target language and your mother tongue.

What is the best part of knowing another language?

There is a saying from China that to learn a language is to have one more window from which to look at the world, and I think that is the best way to describe what it is like.

And as the journalist Flora Lewis said, “Learning another language is not only learning different words for the same thing, but learning another way to think about things.” It’s like when you’re playing a video game and parts of the map that were dark before start to light up. New areas of unexplored mental terrain suddenly reveal themselves to you.

It feels like I started seeing the world with fresh eyes, through the eyes of a child, awe-inspired and struck by wonder, more powerfully and more often.7

I want to end with a story. It was 2022, and my last day of studying abroad in Barcelona. My friend and I went to play basketball at a court near our apartment. The sun was shining, palm trees were swinging, and there was a certain melancholy hanging on my mind about the magical trip coming to an end.

After some time shooting around, I saw a young Spanish boy shooting on the other basket, while his mom watched. He looked about five years old. I went to rebound for him, so he could get more shots up. As I did, I noticed his basketball wasn’t regulation size, and was in rough shape.

A month and a half earlier, I had bought a nice, new full-sized ball. Why try to bring it back on the plane, when I could give it to this kid?

“Hola, tengo que volver a mi país, a los Estados Unidos. Pero no puedo traer esta pelota en el vuelo. ¿Quieres esta pelota?”8 I said.

The way this kid’s face lit up was one of the best sights of my life. His eyes beamed with excitement as he stretched his hands out for the ball.

Walking away from the court, my friend and I didn’t say anything for a while. It was a moment that didn’t need words.

I stayed up all night that night, so I could sleep on my flight that was leaving at 7 A.M. I spent the early morning hours in my room, listening to music. Every time I thought about the happy little Spanish kid, I started weeping. It was strange. Strange because I was dying laughing at the same time. It felt so good.

It is because of stories like this that I’ll never tire of talking about all things language learning. To have Spanish or Mandarin or French or whatever other language in your back pocket is to become part of a club of people you never would have otherwise been able to connect with. And it’s more than that too. It is to feel a deeper kinship with all of mankind. It is to pour gasoline on the fire of your intellectual curiosity. It is to see more beauty in the world.

And I still have a why going forward with it: the main one being that I want to raise my future children bilingual.

This is all in reference to the CEFR, or Common European Framework of Reference for Languages, which is the standardized set of guidelines for measuring skill in a language. A1 and A2 are beginner levels, B1 and B2 are intermediate levels, and C1 and C2 are advanced levels.

Although I typically enjoyed and did well in my Spanish classes in middle school and early high school, I wasn’t serious about learning the language until my senior year, in which I took an advanced placement course. And once I declared as a double major in college at some point during my freshman year, my heart was set on becoming a Spanish speaker.

Once you start consuming content made for native speakers, the key is to pay attention to stuff that you would listen to or read in English anyway, stuff you’re already interested in. It sounds obvious, yet you’ll run into people not only struggling to understand their target language but also boring themselves because they don’t care about the content.

But if I could imagine an example, here it is: Every day, use Google Translate to learn and write down, say, ten new phrases. (Then you could use the speaking feature on Google Translate to hear the pronunciation, then practice pronouncing it yourself, and do this until you can say your ten written phrases from memory with some confidence). The next day, write ten more phrases while still practicing the ones you’ve already learned, and repeat this ad infinitum. Just a thought. I did this process a bit when I was learning some very basic Italian in preparation for a trip to Italy.

With that said, I feel obligated to say that, of course, it’s possible to learn a language more easily and faster than I did. You could have a higher language aptitude, you could live for longer in a foreign country, or you could just be better at language learning!

There is also an intimate connection between language learning and philosophy. In short, to learn another language is to always ask “what does that mean?”

“Hello, I have to go back to my country, to the United States. But I can’t bring this ball on the flight. Do you want this ball?”

Such a brilliant read here, Jeff - and congratulations on passing C1. That’s a huge achievement. We found ourselves nodding along at several parts, from your description of the sheer amount of time and effort it takes to learn a language to such an advanced level, to the experiences and relationships which open up to you once you get there.

We think you’d really enjoy our new newsletter, El Boletín, which curates interesting, native articles and videos for advanced Spanish learners. If you’d like to become a free subscriber, we’d love to bump you up to the paid tier, completely free, for the first issue when it drops on Saturday morning. Happy to extend that to any of your subscribers, too.

Congratulations again on your achievement. 👍🏻

Don Jeffery