The Wisdom of Christ

Feliz Navidad

My brother and I recently took a weekend trip to Connecticut to visit a friend. As we drove, a random Spotify Christmas music playlist was on shuffle. The song Hark! The Herald Angels Sing came on as we whipped around a sharp bend on the dark highway. Suddenly in front of us, atop a large hill, stood a massive cross, illuminated in purple. The timing was uncanny — the exact moment the lyrics “glory to the newborn king” filled our car, there it was. I didn’t know what to do or say. I gave my brother a fist bump and we laughed.

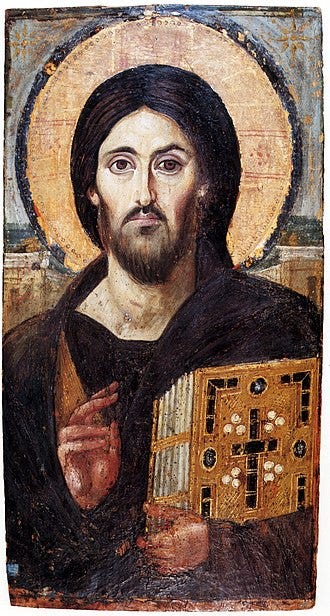

This moment added to my collection of cherished Christmas memories, a season that always made me curious. As a kid, I wondered why that sneaky Saint Nick never finished the cookies we left for him. I also loved the absurd decorations my father and I would set up in our yard — an inflatable globe of elves on a candy cane merry-go-round was a classic one.1 These scenes were a strong contrast to the mysterious man from the Middle East who underpinned the holiday’s deeper meaning. And at some point, as I began to question why Santa didn’t bring wealth to kids in poverty, I also questioned why this true figure of Christianity didn’t make a quick televised appearance to silence the doubters.

As I grew older, this innocent curiosity turned into a cynical skepticism, especially after attending a Catholic high school. There, faith seemed to crumble as quickly as the building itself. Ceilings would literally collapse, and yet the church would still snatch much of our limited funds for themselves. Stuffy religious ideals being pushed under such conditions felt hollow and meaningless. Rebellious student behavior was a natural response. It was exacerbated by administrators who would dig into the personal lives of students, stalking our social media, warning us they knew about our parties. This, of course, only added to the thrill of being reckless. At the end of every day we would all recite a prayer through the intercom only to be rolling dice amongst red eyes in the locker room minutes later. Living in this environment for years fueled my intense disillusionment with “Christians.”

The school has since shut down. But the disillusionment still stings. Imagine that as your teenage experience. Then you read the ideas of, say, Nietzsche and Schopenhauer. You learn about the Crusades and the Inquisition, devilish priests and witch hunts. You read about Eastern belief systems, and grasp the basics of evolutionary theory. You recognize the indifference of nature, the cruelty of some beings, the cold randomness of tragedies. How can you not conclude that Christianity is only for the hopelessly naïve or the foolishly dogmatic?

However, I’ve since recognized the insane arrogance of that conclusion. “Two kinds of fools” said Naval Ravikant, “those who take religion literally, and those who think it has no value.” The latter, more common nowadays, misses out on so much wisdom. For instance, the rich insights on psychology and the human condition that Christianity gifts us. Jordan Peterson’s view that myths are moral in their intent rather than descriptive highlights their Lindy value: religious stories are not primitive humans attempting to make scientific explanations of the world. Rather, they are timeless survival and behavior guides in the form of narrative.

You don’t have to accept Christian stories as the literal truth to accept their incredible value. Needless to say, seeking objective truth should take precedence over everything. But the speed with which people mock and dismiss the value of religious wisdom is a serious modern illness.

Thankfully, I no longer have this illness. And the moment on that Connecticut highway, when the cross appeared at the perfect moment as the perfect Christmas lyrics rang, might seem trivial. Yet it struck me as a profound moment of synchronicity. I bet such “coincidences” can be explained by probability theory. But I don’t care if it was senseless chance. I felt connected to something greater than my brother and I in that special moment.

“You must know that there is nothing higher, or stronger, or sounder, or more useful afterwards in life, than some good memory, especially a memory from childhood, from the parental home. You hear a lot said about your education, yet some such beautiful, sacred memory, preserved from childhood, is perhaps the best education. If a man stores up many such memories to take into life, then he is saved for his whole life.”

— Fyodor Dostoevsky, The Brothers Karamazov, 1880

Merry Christmas Jeff 💝🎄

Surrendering to the Sync

Happy holidays Jeff. I think you're right, even stories with holes can lead our attention in holy directions.